Excavations were

carried out North and West of the Bath (Grid Sections H 18 and

I 17). Among the discoveries was a massive layer of debris,

brought here as landscaping fill to raise the floor level of the

Bath in the later 4th century B.C.

Fig. 99-2. Block grooved for rafters

from the Early Temple of Zeus

with cement left in spaces between now-perished wood (inv. no.

A 451).

The debris

consisted largely, perhaps exclusively, of broken blocks and tiles

from the Early Temple of Zeus that had been destroyed already

in the late 5th century B.C. New information about that

Archaic structure and its history included the use of cement in

the bedding of the tiles of its roof, and the fact that the building

had been destroyed by an intense fire that was, however, confined

to a part of the structure. The debris also produced fragments

of terracotta lion's head water spouts.

Fig. 99-3. Fragments of Corinthian

cover tiles from the Early Temple of Zeus

showing degrees of burning (inv. nos. AT 510, 486, 504, 488).

Fig. 99-4. Fragments of terracotta

lion's head spouts

(inv. nos. AT 464 + AT 461).

A

test trench immediately north of the Bath and beneath this debris

in Section I 17 produced substantial quantities of pottery of

the Geometric period. This is the most intense evidence yet discovered

for activity at Nemea in the 8th century B.C.

Fig. 99-5. Geometric skyphos (inv.

no. P 1640).

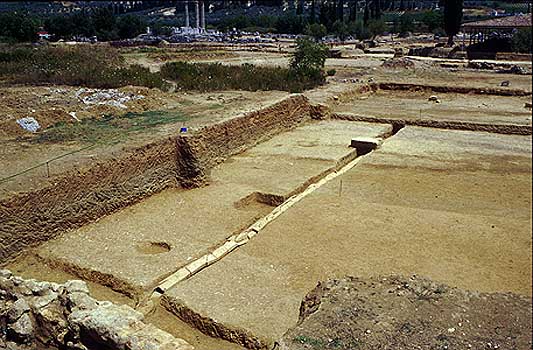

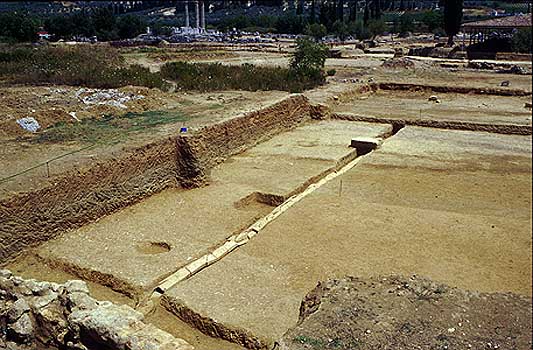

Removal of the debris in Section

H 18 revealed more of the white clay surface that has tentatively

been identified as the track of the Early Stadium of the Nemean

Games.

Fig. 99-6. White clay layer in

Grid Section H 18, from Southeast, with robbing trench at left.

(Return to 2000 news)

The discovery

of the robbing trench which would be appropriate for the early

starting blocks found in 1997 lends credence to the Early Stadium

identification.

Fig. 99-7. Examples of the single-foot-groove

starting blocks of Archaic date

discovered reused as cover-slabs for the drain of the late 4th

century Bath (inv. nos. A 402, A 401).

(Return to 2000 news)

At

the western side of the excavations, in Section E 18, the search

for the ancient hippodrome was frustrated, but a fragment of a

bronze Corinthian helmet was the first piece of defensive armor

discovered at Nemea in 27 years. A fundamental difference

between Olympian Zeus and Nemean Zeus comes into focus.

Fig. 99-8. Fragment of nose guard

of Corinthian helmet (inv. no. BR 1467).

Section

E 18 did reveal a well-preserved stretch of water channel protected

by Corinthian cover tiles exactly like that which feeds the Bath.

Fig. 99-9. Water channel sloping

down toward West in E 18, from Southwest.

(Return to 2000 news)

At

the extreme western side of the area excavated in 1999, the water

channel drops down to run beneath a wall constructed of large

ashlar blocks.

Fig. 99-10. Walls at western edge

of Grid Section E 18, from South.

(Return to 2000 news)

This

and another wall parallel to it were discovered at the end of

the excavation season; plan, purpose and date are still unknown.

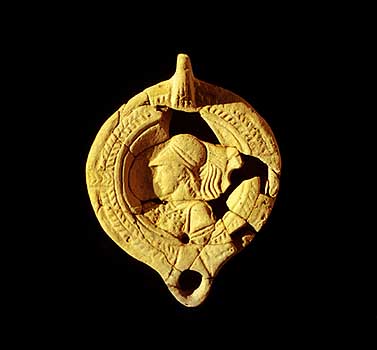

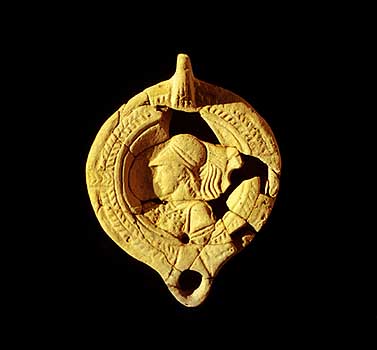

Inside the wall, however, were found several dozen lamps

of the 3rd century after Christ.

Fig. 99-11. Terracotta lamp with

Athena in disc, 3rd century after Christ (inv. no. L 269).

(Return to 2000 news)

(Return to 2002 news)

Non-excavation

activities included the establishment of an educational display

in the ancient Bath where paths are marked with drawings of the

reconstructed rooms and explanatory texts for each.

Fig. 99-12. East room of Bath,

from East.

Reconstruction

of two columns on the northern side of the Temple of Zeus began,

and by the end of 1999 one had reached the mid-point with six

column drums set back in place while the other had two. Both

should be finished and united with their epistyle by the end of

April, 2000.

Fig. 99-13. Temple of Zeus, from

Northwest, November 29, 1999.

(Return to 2000 news)

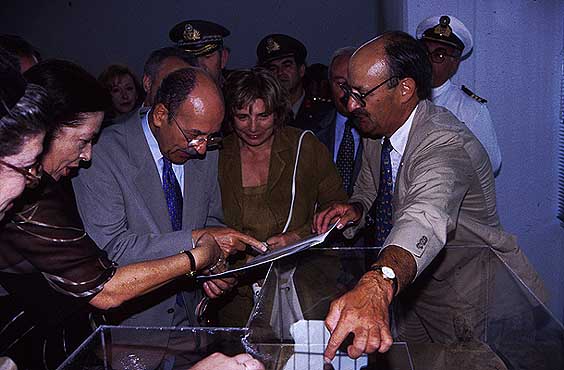

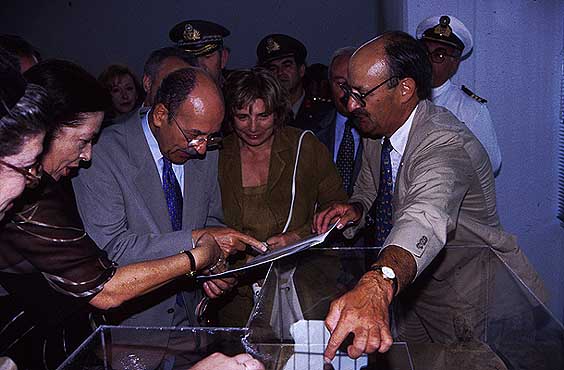

The commencement

of the temple reconstruction and the announcement of the Second

Nemead on June 3-4, 2000, was marked by a visit from the President

of Greece, Kostantinos Stephanopoulos, together with the Minister

of Culture and many other dignitaries.

Fig. 99-14. L-R: Lila Mendone

(Secretary-General of the Ministry of Culture); Elissaveth Spathari

(Ephoros of Antiquities); Kostantinos Stephanopoulos (President

of Greece); and Elissavaeth Papazoe (Minister of Culture) examine

the model of the Stadium in the Nemea Museum as explained by Stephen

Miller (Director of the Excavations).

Update on Excavations: 2000

(To Top)

Three different

activities took place in 2000 at the eastern end of the Temple

of Zeus. The first of these was the continuation of the

reconstruction of two columns on the northern side of the 4th-century

temple (see above, Fig. 99-13).

Fig. 00-1. Temple of Zeus from

the Southwest with 1 1/2 newly re-erected columns

joining the always-standing three, December 18, 2000.

Since the foundations

of the 4th-century temple are not a solid mass, it was possible

to make probes in the open areas between the foundations in an

attempt to recover the plan of the early 6th-century temple.

Fig. 00-2. Probing into the gaps

of the foundations of the 4th-century temple

at its eastern end.

These probes revealed

a clear line of the eastern front of the Early Temple of Zeus,

and substantial evidence for the other three sides of the building.

Fig. 00-3. First step (in middle)

at southeast corner

of the Early Temple of Zeus seen between 4th-century

foundations, from East, with the return of the inner face

of the south wall of the early temple.

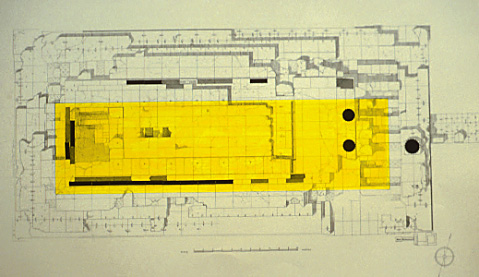

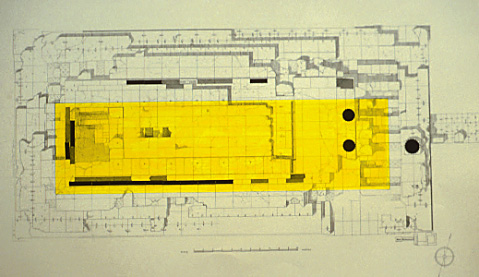

The result

is that the overall size of the Early Temple of Zeus can be estimated

as 9.80 x 35.60 m., with a longitudinal axis that lay parallel

to but south of that of the fourth century temple.

Fig.00-4. Plan of the 4th-century

Temple of Zeus with the area of the Early Temple

of Zeus indicated in yellow.

(Return to 2001 news)

The third area

of work was in front of the temple (Section L 12, see Fig.

99.1) where massive debris of the Early Temple of Zeus had

been used as landscape fill in the late 4th century BC.

Fig. 00-5. Destruction debris east

of the Temple of Zeus during excavation, from Southeast.

This debris contained

many fragments of wall blocks with plaster and painted designs.

Fig. 00-6 Fragment of painted block

from the Early Temple of Zeus,

perhaps with the beak of a bird (inv. no. A 458).

Fig. 00-7. Fragment of painted

block from the Early Temple

of Zeus, perhaps with a human eye in profile, looking left

(inv. no. A 475).

These

fragments, plus the complete absence of any trace of sculpture,

suggest that the pediment of the early temple had a painted scene

on a flat surface which may be relevant to the mention by Euripides,

Hypsipyle to ". . . painted images in the pediment.

. ." The debris also produced other artifacts, the

most interesting of which was a bronze leaf of wild celery, the

crown of victory at the Nemean Games.

Fig. 00-8. Leaf of wild celery,

perhaps from the bronze statue

of an Archaic or Early Classical (500-420 BC) victor in the Nemean

Games

(inv. no. BR 1521).

The

removal of the destruction debris/landscape fill revealed a fine

white clay layer that had been the paving in front of the Early

Temple.

Fig. 00-9. White clay paving in

Section L 12 with wheel markings of ancient carts, from North.

Northwest of the Temple of Zeus

a trial trench was opened which produced a small and curious P-shaped

structure, and many coins and arrowheads.

Fig. 00-10. P-shaped

structure with stub of one

orthostate preserved, in Section H 9, from Northwest.

Fig. 00-11. Sample of bronze arrowheads

from Section H 9

(inv. nos. BR 1500, 1501, 1516, 1539, 1540, 1543, and 1546-49).

Fig. 00-12. Sample of coins found

in Section H 9.

(inv. nos. C4874, C4875, C4905, C4930, C 4933 (all Corinth),/

C4929 and C4909 (Corinth), C4940 (Lokris), C4904 (Phokis), C4911

(Megara),/

C4938 (Phalanna), C4946 (Erythrai), C4878 (Achaian League)

C4951 (Herakleia Trachina), C4925 (Eleusis).

Fig. 00-13. Sample of Sikyonian

coins found in Section H 9

(inv. nos. C4936, C4919, C4920, C4935,/ C4945, C4948, C4949, C4950,/

C4915, C4922, C4926).

Fig. 00-14. Sample of Macedonian

coins found in Section H 9

(inv. nos. C4939, C4912, C4923 (all Philip II),/

C4918 and C4916 (Alexander III), C4924 (Pyrrhos).

In

section E 18, an unlined (single-use) well produced material of

the later 4th century BC.

Fig. 00-15. Pottery from well in

Section E 18: P1684 (skyphos), P1681 (jug),

P1672 (one-handled cup), P1677 (jug), P1666 (mug).

Excavations

continued at the Northwest corner of Section E 18 on the structure

first discovered in 1999 (see Fig. 99-10).

This proves to have been a three-chambered reservoir fed

by a water channel from the Bath (see Fig. 99-9).

Fig. 00-16. Three-chambered reservoir

approached

from right by water channel, from Southwest.

(Return to 2001 news)

The

layers at the top of the reservoir once again produced many lamps

of the early 3rd century after Christ (cf. Fig.

99-11).

Fig. 00-17. Terracotta lamp with

Dionysos in disc

(inv. no. L 282).

(Return to 2002 news)

Fig. 00-18. Terracotta lamp with

Eros in disc

(inv. no. L 279).

(Return to 2002 news)

Although

attention was focused on the central chamber, the reservoir was

not completely excavated in 2000.

Fig. 00-19. Reservoir from South

at end of 2000 season.

(Return to 2001 news)

(Return to 2002 news)

The central chamber,

and therefore the flanking ones as well, is more than 5 meters

deep, and bottom has not yet been reached.

Fig. 00-20. Central chamber of

reservoir at end of season.

(Return to 2001 news)

(Return to 2002 news)

Excavations

in Section F 18 revealed more information about the Hero

Shrine of Opheltes. The artificial mound created in

the 6th century BC extends northward far beyond the rectilinear

outlines of the Early Hellenistic enclosure.

Fig. 00-21. Section F 18 from the

Northwest with Early Hellenistic white porous

enclosure wall of Hero Shrine (upper right) and water channel

from the Bath

parallel to the shrine's north wall. The channel cuts through

the Archaic mound.

A trench through the mound showed

that it was constructed over an early mound of, for the moment,

uncertain date.

Fig. 00-22. Section F 18 from Southwest

with Early Hellenistic water channel at lower right.

Scarp at rear shows surfacing layer of dark red clay that covered

horizontal layers of deliberately

deposited earth which, in turn, covered a more vertical slope

of an earlier mound.

Once again, as in 1997

and 1998, it was discovered that each deliberately laid horizontal

layer contained a single complete vessel, apparently part of a

ritual of sanctification.

Fig. 00-23. Discovery of a jug

(P1661) in an artificial layer of the Hero Shrine's mound.

(return to 2002 news)

Fig. 00-24. Four of the vessels

discovered in the horizontal layers of the Hero Shrine

(foreground, conservation by Mr. Photis Demakis).

(return to 2002 news)

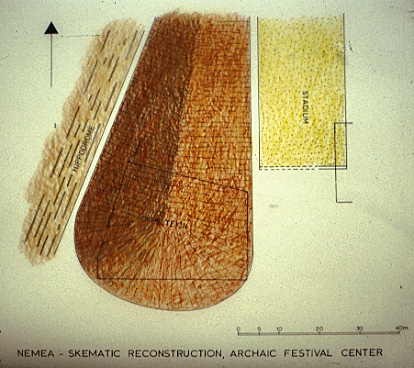

On

the west side of the mound of the Hero Shrine, a series of sandy

layers revealed the traces of the hippodrome of the Archaic and

Classical periods.

Fig. 00-25. Layers with chariot

wheel markings

along the west side of the mound of the Hero Shrine, from North.

Early Hellenistic water channel was set more than a century after

the

formation and passes over the layer with the chariot wheel grooves.

(Return to 2001 news)

These

discoveries, plus that of the Early Stadium in 1999 (see Figs.

99.6 and 99.7), suggest that the Hero

Shrine of Opheltes served not only as a religious center for the

early Nemean Games, but also provided slopes for spectators at

those games.

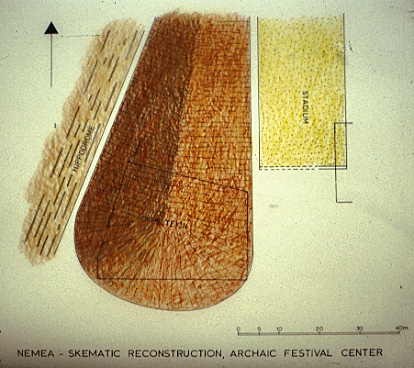

Fig. 00-26. Skematic reconstruction

of Archaic Festival Center at Nemea

with Hero Shrine of Opheltes flanked by hippodrome to left (West)

and early stadium to right.

Update on Excavations: 2001

(To Top)

In

2000 the plan of the Early Temple of Zeus was established (Fig.

00-4), but this plan did not accommodate a wall long visible

at the bottom of the Crypt of the 4th-century Temple and associated

with the Early Temple in publications. In 2001 a small probe carried

out in the Crypt showed conclusively that the wall is not from

the Early Temple, but is a part of the 4th-century building.

Fig. 01-1. Stratigraphy between southern

wall of the 4th-century Crypt and wall further north.

West

of the Temple of Zeus lies the banks of the Byzantine phase of

the Nemea River were dug out and more than a dozen pieces of the

temple were recovered.

Fig. 01-2. Elements of the 4th-century

Temple

recovered from river west of Temple.

The

elongated artificial tumulus/ridge of the infant hero Opheltes

was pursued for more than 100 meters to the north without finding

a definitive end; a total length of about 130 meters can be estimated.

Fig. 01-3. Aerial view of tumulus

with Early Hellenistic enclosure wall around Shrine of Opheltes

in foreground, tumulus/embankment extending northward at least

as far as the small tree with an arrow right (east) of center,

from the south.

The

6th-century mound once again revealed clear indications of ritual

drinking with whole vessels and even sets of vessels carefully

interred.

Fig. 01.4. Bronze oinochoe (BR 1594)

and ceramic skyphoi

in deposit at north end of embankment.

(return to 2002 news)

In the trench

at the northern end of the mound (as far as we uncovered it) was

revealed a north-south curbing wall which seems to be the limit

between the mound on the west and the Early Stadium track on the

east. This is welcome confirmation for our theoretic location

of that early track which was subsequently so damaged and destroyed

by the later river cutting through it.

Fig. 01-5. Curbing wall between

Early Stadium and embankment, from the north.

Several

trenches were excavated along the western side of the mound in

an attempt to locate the hippodrome, that most fugitive of all

Nemean features (see Fig.

00-25). We found clear traces

of chariot tracks in several locations and at several different

levels. Thus, chariots and horses were certainly known in this

area. Unfortunately, we also discovered that the whole area west

of the mound was a flood plain with dozens of layers of sand and

light gravel accumulating over the centuries. Hence, no continuous

flat layer survived that might have preserved wheel ruts over

an extensive horizontal surface. It may be also noted that the

long relatively narrow mound of Opheltes served as a kind of levee

to keep the flood waters away from the Temple.

Fig. 01-6. Wheel ruts in successive

layers of Classical date at western base of tumulus, from south.

The situation

was complicated by the unexpected discovery of yet another starting

line with grooves, like that of the Early Hellenistic Stadium,

for human toes. Although the line is only two blocks long with

space for only two runners, it is clear that no other starting

blocks adjoined these. It seems that we have a practice track

for athletes preparing for the Games in the 4th century.

Fig. 01-7. Starting blocks of Early

Hellenistic date on west side of tumulus

with stratigraphy of artificial tumulus/embankment visible in

scarp behind.

Further to the

west the Reservoir discovered last year (Figs.

00-16, 00-19,

00-20) was

completely excavated.

Fig. 01-8. Aerial view of Reservoir

with aqueduct north of Heroön, and Bath at upper right, from

southwest.

(return to 2002 news)

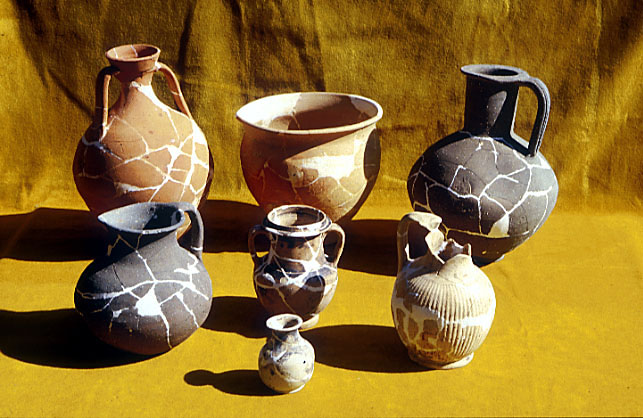

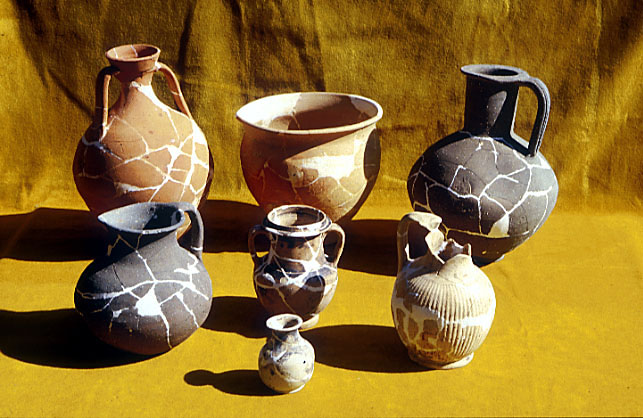

The discoveries in the

three chambers included drinking vessels, jugs, and amphoras which

appear to have been accidentally dropped into the Reservoir by

thirsty ancients.

Fig. 01-9. Ceramic vessels from the

Reservoir.

(P1702, 1728, 1701, 1694, 1704, 1725, 1727)

(Return to 2002 news)

Three discoveries are of particular

importance. One is a lovely bronze ladle with its curved handle

ending in a duck’s head. This piece is paralleled by one

discovered in Macedonia several years ago (See Themelis

and Touratsoglou,

Oi Tãfoi tou Derben€ou

B26.) The two ladles are so similar in design, workmanship,

and size that they appear to have been made in the same workshop,

perhaps by the same artisan.

Fig. 01-10. Ladle (BR 1578).

(Return to 2002 news)

The

second is a bronze Macedonian helmet of the pilos type (BR 1595)

which is now in the conservation department of the National Museum

in Athens. The third is a bronze finger ring which shows a bearded

male about 40 years old, with extremely carefully articulated

hair. The engraver spent much effort which suggests that the model

was an important figure. Given that the ring went into the reservoir

no later than about 275 B.C. (and perhaps a quarter century earlier),

the portrait must be of someone who lived earlier than that time.

Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, is a clear

candidate for this portrait, and the similarities of the ring

portrait with another suggested portrait of Philip on a gold medallaion

in Paris support this identification.

Fig. 01.11. Portrait of Philip(?)

on finger ring (GJ 146)

(Return to 2002 news)

The

completion of the excavation of the Reservoir showed three compartments

of almost identical size: 2.20 x 2.80 and nearly 8 meters deep.

The total capacity was over 140 m.3 although it is doubtful that

they were ever completely full.

Fig. 01.12. View of reservoir from

north.

(Return to 2002 news)

Indeed,

the carefully worked and set blocks of the walls show no traces

of a plaster lining. Our experience shows that the Reservoir can

work as a well, tapping the water table when it is sufficiently

high. On the other hand, the channel that brought water to the

Reservoir from the Bath shows that it must have been necessary

to augment the water supply during times of drought when the water

table was low.

Fig. 01.13. View into reservoir at

completion of excavation.

(Return to 2002 news)

The purpose

for which the Reservoir was intended is unknown. Obviously a large

and reliable supply of water was wanted, but for what? Given the

other indications in this part of the site, one’s thoughts

turn to horses and the desire to assure the owners of these expensive

animals that their participation in the Nemean Games would not

involve a lack of water for them. A number of bronze and iron

pail handles from the Reservoir document the presence of vessels

of an appropriate size to water horses, but no horse trappings

were found. It appears that, at least for the moment, the purpose

of the Reservoir for supplying the horses competing in the Games

must remain an attractive but unproven theory.

Two major improvements were made for visitors. One was the construction

of ramps for wheelchair access to the museum and to the site.

Fig. 01.14. New ramp to museum entrance.

The second improvement was the installation

of a wooden ceiling in the main exhibition hall of the museum

in order to cut down the harsh echo which was interferring with

lectures to groups of tourists.

Fig. 01.15. New wooden ceiling in

main exhibition hall.

Finally, the end of the year saw an inordinate amount of snow

which gave Nemea a rather different aspect than that to which

we are accustomed.

Fig. 01.16. Sanctuary of Zeus from

the south, December 18, 2001.

Update

on Excavations: 2002

(To

Top)

Although

active excavations at Nemea have been suspended for the immediate

future in anticipation of the Athens Olympics in 2004, preparations

for the expected influx of visitors in 2004 and research and publications

of the discoveries of past years were the focus of the work in

2002.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-1. New exhibit of material

from the Hero Shrine of Opheltes [Peop. 02.3]

In

the display areas of the museum, old exhibits were replaced with

more recently discovered material, such as that from the Shrine

of Opheltes (Fig. 02-1; cf. Figs. 00-23, 00-24,

01-4).

.jpg)

Fig. 02-2. Searching through the

sherds from the Shrine of Opheltes. [Peop. 02.7]

All

of the pottery discovered in the shrine was examined and, where

possible, mended into whole shapes. As a result, it became clear

that more than 90% of the vases were drinking cups or wine pitchers

or kraters.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-3. Recording details from

a mixing krater. [Peop. 02.9]

These

vessels were photographed and, in selected cases, drawn. One particularly

interesting piece was a Corinthian krater with the incisions still

remaining, although most of the paint is gone, from a frieze of

horses-and-riders.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-4. New display case with

material from the reservoirs. [Mus. 02.4]

Another

new display which was necessitated by recent discoveries contains

material from the reservoirs discovered southwest of the Temple

of Zeus (Section E 17, Fig. 99-1; Cf. Figs.

00-19, 00-20, 01-8,

01-12, 01-13). The mass

of material more than filled the case (Figs. 99-11,

00-17, OO-18, 01-9,

01-10, 01-11).

.jpg)

Fig. 02-5. Bronze "pilos"

Macedonian type helmet (BR 1595)

To

this material was added a bronze helmet which had been discovered

in 2001, but was taken to Athens for conservation at the time

of discovery. It now is back with its mates in the new museum

case.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-6. Marble lion's tongue

from sima of Temple of Zeus.

Reorganization

of the storage areas in the museum produced a pleasant surprise

in the form of a tongue that once belonged to the marble sima

that ran along the edge of the roof of the temple. It shows the

wear of the rain water that once ran through the lion's mouth

and over the tongue.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-7. Capital about to be

set on newly re-erected column [TZ 02.7]

The

reconstruction of the two columns on the north side of the Temple

of Zeus continued and a number of important stages were realized.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-8. Temple of Zeus from

the Southeast

after completion of two newly reconstructed columns. [TZ 02.72]

As

our research has shown, the three columns that were erected around

330 B.C. have always stood, but the other columns were systematically

knocked down during the reign of Theodosios II (ca. A.D. 435).

Thus, the three columns now have company after some 1,550 years

of loneliness.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-9. The corpse of Hercules

carried off toward the Temple of Zeus.

One

special event during the summer of 2002 was a production of Handel's

"Hercules" in front of the museum with the Temple of

Nemean Zeus in the background. Despite the fears of the group

and their maestro, David Stern, the music was grand and appropriate

to the setting.

.jpg)

Fig. 02-10. The full moon of July

24, 2002, shines on five columns of the temple.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)